Stephanie (Kochmann) Porzecanski 1919-2010 סטפני (קוכמן) פורזקנסקי

This page commemorates the centennial year of Stephanie (née Kochmann) Porzecanski’s birth

Ésta página conmemora el centenario del nacimiento de Stephanie Kochmann de Porzecanski

עמוד זה מציין מאה שנה להולדתה של סטפני פורזקנסקי לבית קוכמן

Stephanie (at right) with her sister Gerda, 1920s

Stephanie (a la derecha) con su hermana Gerda, años 1920

סטפני (מצד ימין) לצד אחותה גרדה, שנות ה1920

Stephanie’s birth certificate

Partida de nacimiento de Stephanie

תעודת הלידה של סטפני

The Kochmann family in a car tour of Potsdam, 1920s

La familia Kochmann paseando por automóvil en Potsdam, años 1920

משפחת קוכמן בטיול רכב בפוטסדאם, שנות ה1920

Our mother, Stephanie (“Steffi”) Meta Kochmann, emigrated with her family from Germany in 1939 on the last ship to leave Hamburg harbour, the Cap Arcona, arriving in Montevideo, Uruguay. The family comprised her father, Walter Kochmann; her mother, Anne Marie (née Alexander) Kochmann; her grandmother, Natalie (née Wertheim) Alexander; and her younger sister, Gerda Kochmann.

She was 19 years old at the time, and soon met the twelve-years older man she would marry and who would become our father, Bernardo Porzecanski, because her family needed their German documents translated into Spanish, and also tutoring in the Spanish language, and he was doing those odd jobs.

At the time, our father, who had arrived in the mid-1920s from Latvia, was a beginning medical student who had taken on various jobs to sustain himself, whether as a glazier, translator, tutor and representative of pharmaceutical companies.

Steffi and Bernardo gave birth to me in January 1943, two years before the latter graduated from medical school. The other two boys followed at long intervals: Arturo in November 1949 and Walter (now Shuki) in July 1959. Steffi had studied to become a kindergarten teacher in Germany prior to her escaping with her family, and together with her sister Gerda, spent time working as a tutor in England thanks to the rescue program for Jewish children known as the Kindertransport.

Raised in Berlin by a wealthy family, she had been sent by her parents to complete her secondary studies in a finishing school in Lausanne, Switzerland, in order to spare her from the discriminatory Nuremberg Race Laws which isolated and disenfranchised German Jews. Steffi was fluent in German, French and English while in Europe, and then in Uruguay she learned and became fluent also in Spanish.

Our father practiced family medicine but also held positions at the University of Uruguay’s School of Medicine, where he became responsible for the production of various vaccines, as well as at the Ministry of Public Health, where he rose to become the head of the Rabies Prevention Institute.

Steffi was a homemaker during the first quarter-century after marrying Bernardo, initially managing the billing of his private medical practice, which took place in the evenings in the apartment that was our home, where our father saw his patients in a room turned into an office. She became very involved with the Uruguay chapter of WIZO, the Women’s International Zionist Organization, and particularly with its Sharon group of younger women, which raised funds for the advancement of Israeli women and their children.

Steffi loved books, especially biographies, and was extremely well read, so after her youngest son Walter started attending elementary school, she pursued her passion by attending the University of Uruguay’s School of Librarianship, completing in 1966 its two-year degree program. Upon graduation, she landed a position as the librarian of the Anglo-Uruguayan Cultural Institute, an offshoot of the British Council.

Several years later, after my wife and I moved permanently to Canada and my middle brother Arturo left for the United States, because the economic and political situation in Uruguay deteriorated greatly, Steffi and Bernardo decided to leave Uruguay and resettle in Canada with my youngest brother. On her way there, Steffi spent one year (1972-73) at the University of Pittsburgh, obtaining a Master’s in Library Science – her ticket to working as a librarian in Canada.

They settled initially in the city of London, Ontario province, where my wife and I were finishing up our medical training and starting a family. Steffi sought work and soon became the librarian at Northern Electric, the forerunner of Northern Telecom and then the now defunct Nortel company. While in London, my father restarted his medical career after revalidating his degree and doing a year of residency, and my brother Walter attended high school.

Soon after, upon finishing my residency in ophthalmology and my wife completing her studies and internship in medicine, we moved with our children to Powell River, a small city on the southern coast of British Columbia province. My parents wanted to follow us out there, but they had to settle for another small city in northern BC, Prince Rupert, because that was where they both found work – she as Chief Librarian of the Prince Rupert Public Library, and he as a physician in a medical clinic.

It would be several years later, in 1978, that my parents would be able to join us in Powell River, BC, where Steffi became a member of the local school board and my father continued to practice medicine. A decade later and already retired, they would move one last time to the beautiful city of Victoria, the provincial capital, because that was where my wife and I (and our three children) had gone to live, since they understandably wanted to keep living close to us in their old age.

Once in Victoria, Steffi and Bernardo became members of the Temple Emanu-El community and she set up a small library for the Jewish community and became involved with the local chapter of the Canadian Hadassah-WIZO. They lived out their lives there, with my father passing on in 1990 and Steffi in 2010.

Two photos of Steffi in 1938 (aged 19)

Dos fotos de Steffi en 1938 (a la edad de 19)

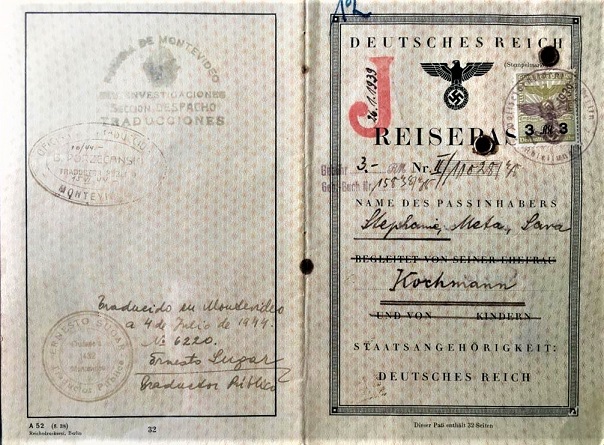

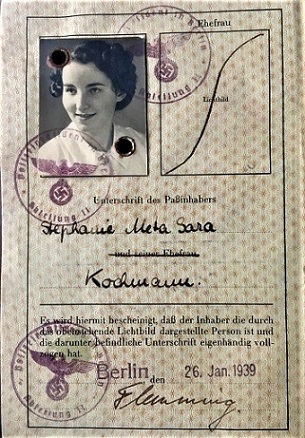

Pages from Stephanie’s last German passport. Note the red J and the name Sara, both used by the Nazi regime to brand all Jews

Páginas del último pasaporte alemán de Stephanie. La J roja y el nombre Sara eran usados por el régimen Nazi para marcar a los judíos

עמודים מתוך הדרכון הגרמני האחרון של סטפני. בולטת האות J האדומה והשם שרה, שניהם שימשו את המשטר הנאצי לסימון היהודים

Nuestra madre, Stephanie (“Steffi”) Meta Kochmann, emigró con su familia desde Alemania en 1939 en el último barco que salió del puerto de Hamburgo, el Cap Arcona, llegando a Montevideo, Uruguay. La familia estaba compuesta por su padre, Walter Kochmann; su madre, Anne Marie (née Alexander) Kochmann; su abuela, Natalie (née Wertheim) Alexander, y su hermana menor, Gerda Kochmann.

En ese momento tenía 19 años y pronto conoció al hombre doce años mayor con el cual se casaría y que se convertiría en nuestro padre, Bernardo Porzecanski, porque su familia necesitaba que sus documentos alemanes fueran traducidos al español, y también instrucción en el idioma español, y él estaba ganando su vida en parte haciendo eso.

Nuestro padre, que había llegado de Letonia en la mitad de los 1920s, era en aquellos momentos un estudiante de medicina que para ganarse un ingreso había tenido diversos oficios como vidriero, traductor, tutor y representante de empresas farmacéuticas.

Steffi y Bernardo me dieron nacimiento en enero del 1943, dos años antes que él se recibiera de médico. Otros dos hijos varones nacieron luego de largos intervalos: Arturo en noviembre del 1949 y Walter (ahora Shuki) en julio de 1959.

Steffi había estudiado para convertirse en maestra de jardín de infantes en Alemania antes de escaparse con su familia y también, junto con su hermana Gerda, había trabajado en Inglaterra como tutora durante un tiempo gracias al programa de rescate para niños judíos conocido como el Kindertransport.

Hija de una familia pudiente de Berlín, ella había sido enviada por sus padres a un colegio en Lausana, Suiza, para cursar sus últimos años de estudios secundarios y para que no tuviera que sufrir la discriminación ordenada por las Leyes Raciales de Nuremberg que aislaron y quitaron derechos civiles a los judíos alemanes. Steffi había aprendido el alemán, francés e inglés en Europa, y en Uruguay aprendió a hablar y escribir muy bien el español.

Nuestro padre era médico general pero también cumplía funciones en la Facultad de Medicina del Uruguay, donde llegó a ser responsable por la fabricación de diversas vacunas en el Instituto de Higiene, y también para el Ministerio de Salud Pública, donde llegó a ser director del Instituto Antirrábico.

Steffi fue una ama de casa en el primer cuarto de siglo luego de su casamiento con Bernardo, aunque inicialmente administraba las cuentas de la práctica médica privada que el realizaba por las tardes y noches en una habitación convertida en oficina dentro del apartamento donde vivíamos. Ella se involucró mucho con la sucursal Uruguay de la organización mundial de mujeres WIZO y fue un miembro muy activo de su grupo Sharon de mueres jóvenes, quienes juntaban fondos para apoyar el progreso de las mujeres en Israel y también el de sus hijos.

A Steffi le encantaban los libros y ella leía mucho, especialmente las biografías, de manera que cuando su último hijo Walter empezó a asistir la escuela primaria, ella decidió cursar estudios de bibliotecnia en la Universidad de la República, de la cual se graduó después de dos años en 1966. Inmediatamente después obtuvo el puesto de bibliotecaria del Instituto Cultural Anglo-Uruguayo, un órgano apoyado por el British Council.

Varios años después, cuando mi esposa y yo nos fuimos para Canadá y mi hermano Arturo para los Estados Unidos, porque la situación económica y política del Uruguay se deterioró mucho, Steffi y Bernardo decidieron emigrar del Uruguay con mi hermano menor y rehacer sus vidas en Canadá. En camino para allá, Steffi pasó un año (1972-73) en Pittsburgh, EE.UU., para obtener su maestría en ciencia bibliotecaria – diploma necesario para ejercer su profesión en Canadá.

Ellos se establecieron inicialmente en la ciudad de London, provincia de Ontario, donde mi esposa y yo estábamos terminando nuestras carreras como médicos y empezando a tener familia. Steffi buscó trabajo y lo encontró como bibliotecaria de Northern Electric, empresa que luego se convirtió en Northern Telecom y luego en la ahora defunta Nortel. Fue en London que mi padre revalidó su título como doctor en medicina después de un año de residencia mientras que mi hermano Walter asistió a la escuela secundaria.

Poco después de yo concluir mi residencia en oftalmología y mi esposa sus estudios e internado en medicina, nos mudamos a Powell River, una pequeña ciudad en la costa sur de la provincia de British Columbia. Mis padres también quisieron mudarse para allá, pero tuvieron que conformarse con otra pequeña ciudad en la costa norte de BC llamada Prince Rupert, porque fue ahí que ambos consiguieron trabajo – ella como jefa de la biblioteca pública de Prince Rupert y el en una clínica médica.

Tuvieron que pasar varios años hasta que, en 1978, mis padres finalmente pudieron reunirse con nosotros en Powell River, donde Steffi trabajó como miembro del directorio de las escuelas públicas de la ciudad y nuestro padre continuó practicando la medicina. Una década después, luego de que nosotros (incluyendo a nuestros tres hijos) nos mudáramos a la hermosa ciudad de Victoria, la capital provincial, Steffi y Bernardo, ya jubilados, hicieron lo mismo para estar cerca de nosotros en su avanzada edad. Habiendo llegado a Victoria, Steffi y Bernardo se hicieron miembros de la comunidad del Templo Emanu-El y ella organizó una pequeña biblioteca para la comunidad judía y se involucró nuevamente con la Hadassah WIZO de Canadá. Pasaron el resto de sus días allí, y mi padre falleció en 1990 y Steffi en 2010.

אמנו, סטפני ("סטפי") מטה קוכמן, היגרה עם משפחתה מגרמניה בשנת 1939 בספינה האחרונה שעזבה את נמל המבורג, ה"קאפ ארקונה", לכיוון מונטווידאו (אורוגואי). משפחתה כללה את אביה, וולטר קוכמן; אמה אן-מארי קוכמן (לבית אלכסנדר); סבתה, נטלי אלכסנדר (לבית וורטהיים); ואחותה הצעירה, גרדה קוכמן.

היא הייתה אז בת 19, ועד מהרה פגשה את הגבר המבוגר ממנה ב12 שנה אשר תינשא לו ויהפוך להיות אבינו, ברנרדו פורזקנסקי. משפחתה הייתה זקוקה לתרגום המסמכים הגרמניים שלהם לספרדית, וגם לשיעורים בשפה זו, והוא עסק בזה בתור עבודה צדדית.

באותה תקופה אבינו, שהגיע באמצע שנות העשרים מלטביה, היה סטודנט מתחיל לרפואה אשר לקח עבודות שונות כדי להתפרנס, בין אם כזגג, מתרגם, מורה, או נציג של חברת תרופות.

סטפי וברנרדו ילדו אותי בינואר 1943, שנתיים לפני שברנרדו סיים את לימודיו בבית הספר לרפואה. שני הבנים האחרים הגיעו במרווחים ארוכים יחסית: ארטורו בנובמבר 1949 וולטר (כיום שוקי) ביולי 1959.

סטפי למדה להיות גננת בגרמניה לפני שנמלטה עם משפחתה, ויחד עם אחותה גרדה בילו זמן בתור אומנות באנגליה בזכות ה"קינדרטרנספורט", התוכנית להצלת ילדים יהודים.

סטפי גדלה בברלין בקרב משפחה אמידה, ונשלחה על ידי הוריה לסיים את לימודיה התיכוניים בבית ספר לגמר בלוזאן, שוויץ, כדי להתחמק מחוקי נירנברג הגזעניים אשר הפלו לרעה את יהודי גרמניה. כבר בעת שהייתה באירופה שלטה בגרמנית, צרפתית ואנגלית, ובאורוגוואי למדה והשתלבה גם בספרדית.

אבינו עסק ברפואת משפחה אך מילא גם תפקידים בפקולטה לרפואה של אוניברסיטת אורוגואי, שם הפך לאחראי על ייצור חיסונים שונים, וכן במשרד הבריאות, שם התמנה לראש המכון ללוחמה בכלבת.

סטפי הייתה עקרת בית ברבע המאה הראשונה לאחר נישואיה לברנרדו, וניהלה תחילה את ספרי החשבונות של הקליניקה הפרטית שלו, שהתקיימה בערבים בביתנו הפרטי, שם קיבל אבינו את מטופליו בחדר שהוסב למשרד. היא הייתה מעורבת מאוד בשלוחה האורוגואית של ויצ"ו, ארגון הנשים הציוני הבינלאומי, ובמיוחד בקבוצת הנשים הצעירות שלה "שרון" אשר גייסה כספים למען נשים ישראליות וילדיהן.

סטפי אהבה ספרים, בעיקר ביוגרפיות, וקראה הרבה, ולכן לאחר שבנה הצעיר וולטר החל ללמוד בבית הספר היסודי, החליטה לממש את תשוקתה לספרים באמצעות לימודי תואר בפקולטה לספרנות באוניברסיטת אורוגואי, וסיימה בשנת 1966 עם תואר ראשון. עם סיום הלימודים היא התקבלה לתפקיד ספרנית של המכון האנגלו-אורוגואי לתרבות, מיסודה של המועצה הבריטית.

מספר שנים לאחר מכן, לאחר שאשתי ואני עברנו לצמיתות לקנדה ואחי האמצעי ארטורו עזב גם הוא לארה"ב, ומכיוון שהמצב הכלכלי והפוליטי באורוגואי הידרדר מאוד, סטפי וברנרדו החליטו לעזוב את אורוגואי ולהתיישב בקנדה עם אחי הצעיר . בדרכה לשם בילתה סטפי שנה אחת (1972-73) באוניברסיטת פיטסבורג, בלימודי תואר שני בספרנות – כרטיס הכניסה שלה לעבודה כספרנית בקנדה.

הם השתקעו תחילה בעיר לונדון, מחוז אונטריו, שם אשתי ואני סיימנו את ההכשרה הרפואית והקמנו משפחה. סטפי חיפשה עבודה והתקבלה כספרנית בחברת נורת'רן אלקטריק, קודמתה של חברת נורת'רן טלקום ואחר כך לחברת הענק נורטל אשר לא קיימת עוד. בזמן ששהה בלונדון, אבי המשיך את הקריירה הרפואית שלו לאחר שחידש את התואר שלו ועשה שנת התמחות, ואחי וולטר למד בתיכון.

זמן קצר לאחר מכן, לאחר שסיימתי את התמחותי ברפואת עיניים ואשתי סיימה את לימודיה ברפואה, עברנו עם ילדינו לפאוול ריבר, עיר קטנה בחופה הדרומי של מחוז קולומביה הבריטית. הוריי רצו להצטרף אבל נאלצו להתפשר על עיר קטנה נוספת בצפון קולומביה הבריטית, פרינס רופרט, כי שם מצאו עבודה – היא כספרנית ראשית של הספרייה העירונית, והוא כרופא משפחה במרפאה.

מספר שנים מאוחר יותר, בשנת 1978, הורי יכלו להצטרף אלינו לפאוול ריבר, שם סטפי נבחרה למועצת ההשכלה המקומית ואבי המשיך לעסוק ברפואה. עשור לאחר מכן פרשו לגמלאות ועברו בפעם אחרונה לעיר היפה ויקטוריה, בירת המחוז, מכיוון שלשם עברנו אשתי, אני ושלושת ילדינו, והם כמובן רצו להיות קרוב אלינו בזקנתם. בוויקטוריה הפכו סטפי וברנארדו לחברים פעילים בבית הכנסת עמנואל וסטפי הקימה ספריה קטנה לקהילה היהודית והשתתפה בקבוצה המקומית של הדסה-ויצ"ו הקנדית. הם בילו את שארית חייהם שם: אבי נפטר בשנת 1990, וסטפי בשנת 2010.

Steffi in Pocitos beach, Montevideo, ca. 1940

Steffi en la playa de Pocitos, Montevideo, por 1940

Two photos of Steffi with her family during the 1950s

Dos fotos de Steffi con su familia en la década de 1950

שני תצלומים של סטפי ומשפחתה בשנות ה1950

Two photos of Steffi with her family during the 1960s

Dos fotos de Steffi con su familia en la década de 1960

שני תצלומים של סטפי ומשפחתה בשנות ה1960

Steffi’s Bachelor in Library Science diploma, 1966

El primer diploma de Steffi en bibliotecnia, 1966

תעודת תואר ראשון של סטפי בספרנות, 1966

Stephanie with her first grandchild, Ilana (1971)

Stephanie con su primer nieta Ilana en 1971

סטפני עם נכדתה הראשונה אילנה, 1971

With her husband Bernardo in Victoria, 1989

Con su marido Bernardo en Victoria, 1989

עם בעלה ברנרדו בוויקטוריה, 1989

Trabajé cinco años con la Señora Steffi, fue muy buena patrona.

Me enseñó a no discriminar a nadie, a aceptar cada persona como era y a ser muy disciplinada.

Ella era bastante exigente con la limpieza y el orden pero todo eso a mí me hizo mucho bien a lo largo de toda mi vida.

Siempre los recuerdo a todos con mucho cariño y a ella especialmente cada 19 de octubre y brindo por su día porque tengo mi compadre y sobrino que cumple el mismo día que ella.

A todos les doy las gracias y para ella siempre tengo una oración y agradecimiento por todo lo que me enseñó.

From Elba Fonseca, Stephanie’s maid in Montevideo during 1963-68:

I worked with Mrs. Steffi for five years, she was a very good employer.

She taught me not to discriminate against anyone, to accept each person as he was and to be very disciplined.

She was quite demanding with cleanliness and order but all that did me a lot of good throughout my life.

I always remember everyone with love and her especially her every October 19, and toast her on that day because my godfather and nephew share the same birthday.

I thank you all, and I always have a prayer for her and thanks for everything she taught me.

עבדתי עם גברת סטפי חמש שנים, היא הייתה מעסיקה טובה מאוד.

היא לימדה אותי לא להפלות אף אחד, לקבל כל אדם כמו שהוא, וכן משמעת עצמית.

היא הייתה די תובענית מבחינת סדר וניקיון, אבל זה עזר לי לאורך חיי.

אני תמיד זוכרת את כולם באהבה, ואותה במיוחד בכל 19 באוקטובר, בו אני מרימה כוסית לזכרה, כי סנדקי/אחייני חולק את אותו יום הולדת.

אני מודה לכולכם ובשבילה תמיד יש לי תפילה ותודה על כל מה שלימדה אותי.

Stephanie’s grave in Victoria

Tumba de Stephanie en Victoria

קברה של סטפני בוויקטוריה

Hay quienes transitan por la vida recibiendo sus duros golpes sin mayores reacciones, lamentándose siempre de su suerte. Pero este nunca ha sido el caso de Tía Steffi. Por el contrario, ella fue un ejemplo de superación ante la adversidad, valentía ante los riesgos y firme decisión ante la incertidumbre.

Destinada a llevar una tranquila vida, reservada a miembros de una acomodada familia, en un entorno casi ideal, en lo que debería ser un mundo perfecto, un país donde sus antepasados vivieron durante siglos, cuya lengua y cultura le eran queridos y propios; vio de pronto su entorno convertirse en una pesadilla de la cual no era posible despertar.

Obligada a marchar al exilio en su juventud, tuvo aun la suerte de huir de aquella demencial realidad junto a su familia, para llegar a un lejano y pequeño país sudamericano, ajeno en sus costumbres, clima y gentes, a donde en circunstancias normales, jamás hubiera elegido vivir. Pero así salvaron su vida, la suya y la de su familia. Decidida a sacar el mejor partido de esa situación, aceptó su nueva existencia, aprendió el idioma perfectamente, se casó y formó una familia ejemplar, de la cual cuidó solícitamente y aun continuó sus estudios recibiéndose de bibliotecaria para ejercer dicha profesión, a través de la cual pudo dedicarse a su pasión: la lectura y los libros.

Recuerdo muy bien que nos prestaba de la Biblioteca del Anglo libros seleccionados, uno más interesante que el otro, y que si bien estaban en inglés, destinados a ser leídos por mis padres, yo los leía o intentaba leer, aun siendo niño. Estas lecturas contribuyeron a mejorar mi conocimiento de dicho idioma, más allá de los básicos cursos escolares.

Recuerdo además, que un verano nos anotó con Walter en la Biblioteca Municipal, para que fuéramos desarrollando el gusto por la lectura, al tiempo de incorporar el sentido de la responsabilidad, al tomar prestado y saber devolver los ejemplares a su debido tiempo.

En las numerosas tardes de los sábados, durante las visitas a su casa, donde concurría feliz a jugar con Walter, siempre me hizo sentir como que estaba en mi segundo hogar. Y no puedo dejar de mencionar como de vez en cuando pasaba alegres días veraniegos en el precioso chalet de La Paloma, “Los Álamos”, especialmente aquel memorable verano de 1969 a 1970 donde la pasamos tan bien y donde me comunicó, lo más casualmente posible para no dejarme entristecido, que habían tomado la decisión de emigrar, en un par de años, a los EE.UU.

Mi primer gran viaje lo hice en diciembre de 1978 a Vancouver, para visitarlo a Walter y luego a Prince Rupert, BC, donde me reencontré con los tíos Steffi y Bernardo. Fue todo un acontecimiento, puesto que además del feliz reencuentro, jamás había estado en un entorno y geografía tan extraordinarios y donde además tuve la satisfacción de colaborar, digamos lo mejor que pude, más entusiasta que eficiente, lo admito, en la mudanza a Powell River. Allí nos reunimos con Ale y Ana y con las aun pequeñas niñas Ilana y Ayelet. Nuevos cambios, nuevos desafíos, que tía Steffi supo superar con decisión y firmeza, un nuevo lugar donde una vez más rehacer su hogar y retornar a sus actividades como bibliotecaria. Allí donde una vez más, ella me hizo sentir que había sido cariñosamente recibido.

En mi viaje de retorno me llevó hasta el aeropuerto local donde tomé un vuelo regional hacia Vancouver. Allí, aun se tomó el tiempo para comprar chocolates y bombones para que los llevara como su regalo a mamá y papá. Al elegir cada artículo, tomaba la precaución de leer su procedencia. Al final se decidió entre otras cosas por una muy bonita caja de bombones de Finlandia. Mientras leía cada rótulo, me explicaba, “Evito comprar nada alemán, lo que viví allá en aquellos años no lo olvidaré jamás. Tal vez tu mamá no lo vivió de la misma forma, porque era muy joven cuando dejó aquel país, pero yo era mayor y muy consciente de lo que pasaba; las humillaciones que vi, las recordaré por siempre”.

En este mundo en el que vivimos, tan cambiante, tan distinto, recuerdo a tía Steffi y tío Bernardo, que aun a una edad en la que habían dejado bien atrás su juventud, supieron reformular y readaptar su vida en forma tan proactiva y dinámica: nunca mirando hacia atrás, siempre hacia adelante!

Que sea su memoria bendita para siempre

From Rafael Rosenberg, Walter's friend and son of Steffi’s friend Yael Rosenberg:

Some go through life taking its blows without reacting, lamenting their fate. But this has never been the case with Aunt Steffi.On the contrary, she was an example of overcoming adversity, courage in the face of risks and firm decisions in the face of uncertainty.

Destined to lead a quiet life, reserved for members of a wealthy family in an almost ideal environment, in what should have been a perfect world and a country where her ancestors had lived for centuries, whose language and culture they held dear and considered their own, she saw her surroundings suddenly become a nightmare from which she could not wake up.

Forced into exile in her youth, she was lucky to flee from that insane reality with her family and to reach a distant and small South American country, with customs, climate and people that were strange to her, and where under normal circumstances she would have never lived. But this saved her life and her family’s. Determined to get the best out of the situation, she accepted her new life, learned the language perfectly, married and raised a wonderful family, yet continued her librarianship studies to be able to practice that profession, through which she could fulfill her passion for reading and books

I remember very well that she would loan us a selection of books from the Anglo library, one more interesting than the other, and although they were in English, intended to be read by my parents, I read or tried to read them, even as a child. These readings contributed to improve my knowledge of that language beyond what was taught in school.

I also remember that one summer she registered Walter and me in the Municipal Library, so that we could develop a taste for reading, while promoting responsibility by borrowing and returning the books on time.

On many Saturday afternoons during visits to her home, where I was happy to play with Walter, she always made me feel like I was in my second home. And I cannot fail to mention how from time to time I spent happy summer days in the beautiful cottage in La Paloma, “Los Alamos,” especially that memorable summer of 1969-70 where we had such a good time and where she communicated to me, as casually as possible in order not to sadden me, that they had made the decision to emigrate, in a couple of years, to the U.S.

My first big overseas trip was in December 1978 to Vancouver, to visit Walter and then Prince Rupert, B.C., where I met up with Steffi and Bernardo. It was quite an event, since in addition to the happy reunion, I had never been in such an extraordinary environment and geography, and I also had the satisfaction of helping – let's say as best I could, with more enthusiasm than efficiency, I admit – with the move to Powell River. There we met Ale and Ana and the still small girls Ilana and Ayelet. New changes, new challenges, that Aunt Steffi knew how to overcome with determination and firmness, a new place where once again to rebuild her home and return to her activities as a librarian. Where once again, she made me feel that I had been affectionately received.

On my return trip she took me to the local airport where I took a regional flight to Vancouver. There, she still took the time to buy chocolates to take as a gift to mom and dad. When choosing each article, she took the precaution of reading its origin. In the end she decided among other things to get a very nice box of chocolates from Finland. While reading each label, she explained to me: “I avoid buying anything German, I will never forget what I went through in those years. Maybe your mother did not live it the same way, because she was very young when she left the country, but I was older and very aware of what was happening, and the humiliations I saw I will remember forever.”

In this world in which we live, so changing, so different, I remember Aunt Steffi and Uncle Bernardo, that even at an age when they had left their youth well behind, they knew how to reformulate and readjust their life in such a proactive and dynamic way: never looking back, always forward!

May her memory be forever blessed

יש כאלה שבמהלך חייהם סופגים מכות קשות, אינם מגיבים באופן משמעותי, ומקוננים על מר גורלם. אך זה מעולם לא היה מצבה של דודה סטפי. נהפוך הוא, היא הייתה דוגמא להתגברות על מצוקות, אומץ לב מול סיכונים והחלטיות נחרצת אל מול חוסר וודאות.

היא נועדה לנהל חיים שקטים, שמורים למשפחה עשירה, בסביבה כמעט אידיאלית, במה שצריך היה להיות עולם מושלם, מדינה בה חיו אבותיה במשך מאות שנים, ששפתה ותרבותה היו יקרים ושייכים להם; היא ראתה את סביבתה פתאום הופכת לסיוט שממנו לא ניתן היה להתעורר.

כשהיא נאלצת לצאת לגלות בצעירותה, התמזל מזלה לברוח מאותה מציאות מטורפת עם משפחתה, ולהגיע למדינה דרום אמריקאית רחוקה וקטנה, בעלת מנהגים, אקלים ועם שהיו זרים לה לחלוטין, היכן שבנסיבות רגילות לעולם לא הייתה בוחרת לחיות. אך בכך ניצלו חייה וחיי משפחתה. נחושה בדעתה להפיק את המיטב מאותה סיטואציה, היא קיבלה את מצבה החדש, למדה את השפה החדשה בצורה מושלמת, התחתנה והקימה משפחה למופת, והכול תוך זה שהיא דואגת לעצמה וממשיכה בלימודים לקבלת תואר בספרנות, ומתחילה לעסוק במקצוע הזה, שבאמצעותו התאפשר לה להקדיש עצמה לתשוקתה לקריאה ולספרים.

זכור לי היטב שהיא הייתה משאילה לנו ספרים נבחרים מהספרייה של המכון אנגלו, כל אחד יותר מעניין מהשני, ועל אף שהם היו באנגלית ונועדו להיקרא על ידי הוריי, קראתי או ניסיתי לקרוא אותם, אפילו כילד. ניסיונות אלה תרמו לשיפור הידע שלי בשפה זו, מעבר ללימודים הבסיסיים שבבית הספר.

אני זוכר גם שבקיץ אחד היא רשמה אותי ואת וולטר לספרייה העירונית, על מנת שנפתח תאווה לקריאה, תוך שילוב תחושת האחריות על ידי זה שמשאילים ומחזירים את הספרים בזמן.

בכל הביקורים שלי בביתו של וולטר, שם ביליתי שעות אחר צהריים רבות בשבתות כדי לשחק, היא תמיד גרמה לי להרגיש שאני נמצא בבית השני שלי. ואני לא יכול שלא להיזכר איך ביליתי מעת לעת ימי קיץ שמחים בקוטג' היפה שבלה פלומה, ”לוס אלמוס“, במיוחד באותו קיץ בלתי נשכח של 1969-70 בו היה לנו כל כך טוב והיא מסרה לי, כלאחר יד כנראה בשביל לא להעציב אותי, שהם קיבלו את ההחלטה להגר, בעוד כמה שנים, לארצות הברית.

הטיול הגדול הראשון שלי היה בדצמבר 1978 לוונקובר, לבקר את וולטר ואז לפרינס רופרט, קולומביה הבריטית, שם נפגשתי עם הדודים סטפי וברנרדו. זה היה אירוע משמעותי, שכן בנוסף למפגש המאושר, מעולם לא הייתי בסביבה וגאוגרפיה כה יוצאת דופן ושם גם היה לי הסיפוק של לשתף פעולה – בואו נאמר הכי טוב שיכולתי, נלהב יותר מיעיל, אני מודה בזה – במעבר לפאוול ריבר. שם פגשנו את אלה ואנה ואת אילנה ואיילת, עדיין ילדות קטנות. שינויים חדשים, אתגרים חדשים, שדודה סטפי ידעה להתגבר עליהם בנחישות ובקשיחות, מקום חדש שוב לבנות את ביתה ולחזור לפעילותה כספרנית. ושם היא שוב גרמה לי להרגיש מאד אהוב.

בדרכי חזרה היא לקחה אותי לשדה התעופה המקומי בו לקחתי טיסה אזורית לוונקובר. שם היא עדיין לקחה את הזמן לקנות שוקולדים לקחת במתנה לאמא ואבא. בבחינת כל פריט הקפידה בזהירות לקרוא את ארץ מוצאו. בסופו של דבר היא בחרה בין היתר קופסת שוקולדים נחמדה מאד תוצרת פינלנד. תוך כדי קריאת התוויות הסבירה לי, ”אני נמנעת מלקנות תוצרת גרמניה, מה שעברתי שם באותן שנים לעולם לא אשכח. אולי אמך לא חיה את זה באותה צורה, כי הייתה צעירה מאוד כשעזבה את המדינה, אבל אני הייתי יותר בוגרת ומודעת מאוד למה שקורה; ההשפלות שראיתי, אזכור לעד”.

בעולם הזה בו אנו חיים, שמשתנה כל הזמן, כל כך שונה, אני זוכר את דודה סטפי ואת הדוד ברנרדו, שגם בגיל בו הם השאירו את נעוריהם הרחק מאחור, ידעו להקים מחדש את חייהם בצורה פרואקטיבית ודינאמית כל כך: אף פעם לא להסתכל אחורה, תמיד קדימה!

יהיה זכרה מבורך לעד